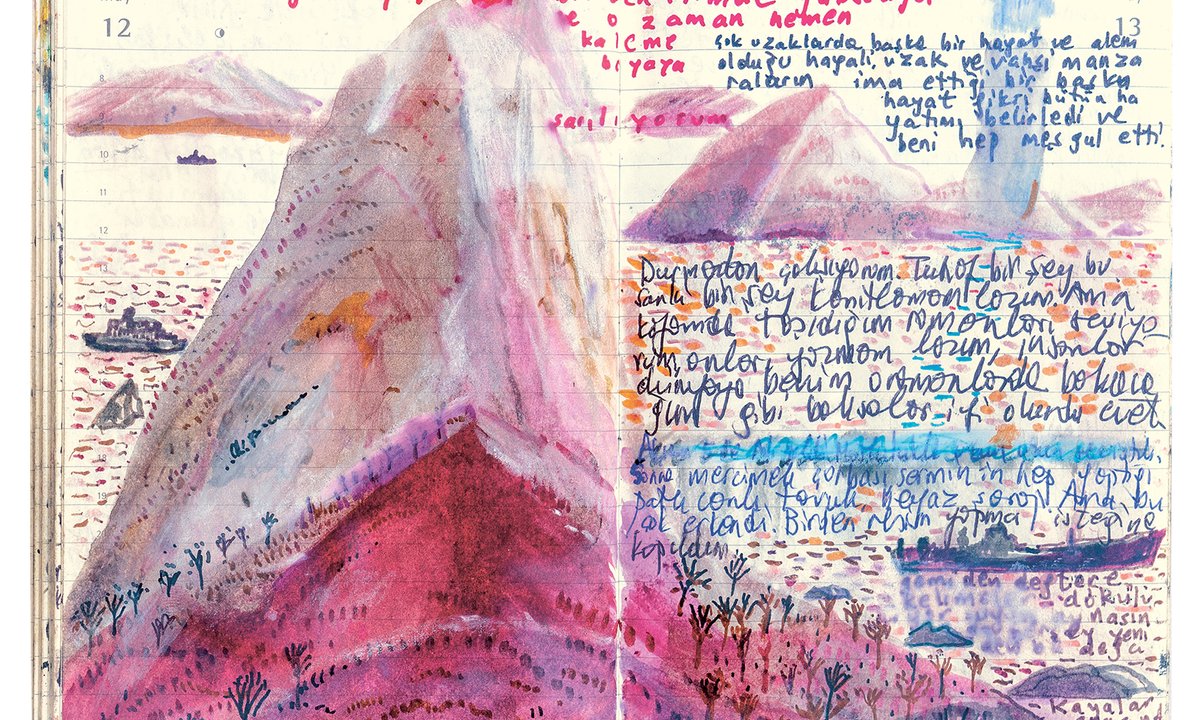

Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s most well-known dwelling novelist, has at all times had a secret ardour. The creator of best-selling books similar to My Title is Pink, Nights of Plague and Snow can also be an artist, producing quite a few illustrated notebooks protecting the interval from 2009 to 2022. Daily throughout that point, Pamuk wrote and drew in his Moleskine notebooks, creating William Blake-esque doodles that mirror a spread of experiences similar to taking pals to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Artwork or travels to international locations similar to India.

These illustrations, together with Pamuk’s candid texts, have been mixed into one quantity entitled Recollections of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks. “Ekin Oklap’s translations swarm playfully across the reproductions of the pocket book pages, organized in cloud-like type,” says a overview within the Occasions Literary Complement.

“Recollections of Distant Mountains is a range from the pictured pages of my journals,” Pamuk says. “Within the 400-page e book, the images are associated to one another and to texts that encompass them thematically, or by a sense or a coincidence. There’s a continuity of phrases and photos that I care about. The pages observe and narrate emotions, goals, nightmares, sentiments, travels, observations—all in color.”

Pamuk makes use of brush-tipped pens, pencils, crayons and watercolours to create the illustrations. “Typically as I write on a web page, I go away an area for a drawing I’ll later make. Typically I write over a painted double web page. Texts don’t clarify the images nor the images illustrate the texts,” he says.

Poetic order

The duty has been difficult, stresses Pamuk, who provides that choosing the pages from greater than 30 pocket book volumes was a “main labour”. Placing them in a “poetic” order in order that they counsel a narrative was one other check, he says. “I didn’t put the pages in a chronological order. I lined them up by themes, by topics, by sentiments, by locations and even by colors. The reader, after a web page that was created in 2016, might subsequent examine the same sentiment expressed otherwise with an image made in 2009.”

The e book additionally covers tough episodes within the creator’s life. In a 2005 interview Pamuk made feedback concerning the 1915 mass killings of Armenians and Kurds within the Ottoman Empire; he was attacked within the Turkish press and subsequently given safety within the type of three bodyguards. He annotates a road scene drawing from 2020, saying: “Right here is the court docket the place I stood trial in 2005 for speaking concerning the Armenian genocide. Individuals threw stones at us on the best way out.” In different entries, he describes making work within the studio of Inci Eviner, who represented Turkey on the Venice Biennale in 2019.

Pamuk needed to be a painter however was steered in direction of structurePicture: Jerry Bauer

Pamuk’s enthusiasm for artwork lay dormant for a few years. “I needed to be a painter till the age of twenty-two,” he says. “My grandfather, my father and uncles have been all civil engineers. I used to be anticipated to go to the identical school, Istanbul Technical College. Since I used to be the black sheep, the artist within the household of civil engineers, all of them stated I needed to go to the identical college however research structure as a substitute of civil engineering. Out of the blue, on the age of twenty-two, I killed the painter in me and commenced writing novels. In the long run the painter in me didn’t die both. However he was shy and dealing secretly.”

The notebooks additionally spring from one other main mission, specifically Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, which opened in 2012 and is predicated on his 2008 novel of the identical identify (a love story by which the narrator Kemal collects quite a few gadgets owned by his cousin Füsun). Named the 2014 European Museum of the Yr, the museum homes wood containers associated to the e book’s 83 chapters. Every field is full of gadgets—each readymade items and commissioned artistic endeavors—that mirror each chapter, thereby protecting a 30-year interval within the historical past of contemporary Istanbul from 1975, when the novel begins.

Out of the artwork closet

“After it opened in Istanbul, I by no means put any of my very own cash in direction of the museum, which prices round €11 for a ticket,” Pamuk says. “After seeing the success of the museum and publishing its catalogue, Innocence of Objects, I assumed that I now can get out of the closet as an artist and may maybe exhibit my creative work. Publishing these choices from my diaries was not a simple choice.”

A travelling exhibition primarily based on the Museum of Innocence and different works Pamuk has made prior to now 25 years just lately opened on the Dox Centre for Up to date Artwork in Prague (The Comfort of Objects, till 6 April) after stints on the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden and the Lenbachhaus in Munich. “The curators Matthias Mühling and Melanie Vietmeier got here to Istanbul, appeared into my archives and located issues—many notebooks, photographs, watercolours, sketches, panorama work.”

Pamuk’s journals are a part of a protracted custom of literary diaries. “Writers’ diaries curiosity me. Have a look at Leo Tolstoy; he was a manic diary keeper however the unhappy factor about his diaries is that one of the best components, that I might most care about, aren’t written. When he was writing his greatest novels, Tolstoy didn’t write in his journals. Virginia Woolf is one other hero of mine who is a superb diarist,” he says. “Now, retaining a journal—utilizing the diary type—might even be a manner of inventing an experimental literary house.”

• Recollections of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks, by Orhan Pamuk (translated by Ekin Oklap), Faber, 384pp, £35 (hb)

| by Jessy quiee | The Capital | Mar, 2025

| by Jessy quiee | The Capital | Mar, 2025